Eight Misconceptions About El Niño (and La Niña) Posted by Francesco Fiondella on June 30, 2014

For years, people have been pointing to El Niño as the culprit behind floods, droughts, famines, economic failures, and record-breaking global heat. Can a single climate phenomenon really cause all these events? Is the world just a step away from disaster when El Niño conditions develop? What exactly is this important climate phenomenon and why should society care about it? Who will be most affected? We address these questions as well as clear up some common misconceptions about El Niño, La Niña, and everything in between!

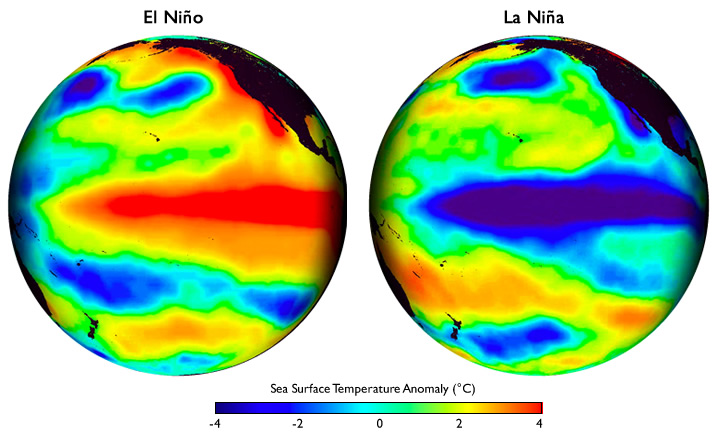

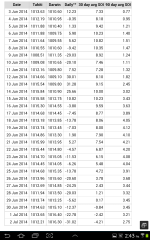

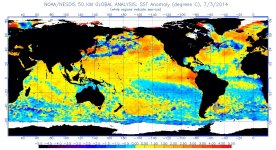

First, the basics. El Niño refers to the occasional warming of the eastern and central Pacific Ocean around the equator (see image below). The warmer water tends to get only 1 to 3 degrees Celsius above the average sea-surface temperatures for that area, although in the very strong El Niño of 1997-98, it reached 5 degrees or more above average in some locations. La Niña is the climate counterpart to El Niño– a

yin to its

yang, so to speak. A La Niña is defined by

cooler-than-normal sea-surface temperatures across much of the equatorial eastern and central Pacific. El Niño and La Niña episodes each tend to last roughly a year, although occasionally they may last 18 months or longer.

These global maps centered on the Pacific Ocean show patterns of sea surface temperature during El Niño and La Niña episodes. The colors along the equator show areas that are warmer or cooler than the long-term average. Image courtesy of Climate.gov

The Pacific is the largest ocean on the planet, so a significant change in its normal pattern of surface temperatures would lead to corresponding changes in atmospheric winds. This can have consequences for temperature, rainfall and vegetation in faraway places. In normal years, trade winds push warm water—and its associated heavier rainfall—westward toward Indonesia. The warmer waters in the west and relatively colder waters in the east Pacific reinforce the pattern and strength of the trade winds. But during an El Niño, which occurs on average once every three-to-five years, the winds peter out and can even reverse direction, bringing the rains toward South America instead. This is why we typically associate El Niño with drought in Indonesia and Australia and flooding in Peru. We have observed enough El Niño events by now that we know these changing climate conditions, combined with other factors, can have serious impacts on society, such as reduced crop harvests, wildfires, or loss of life and property in floods. There is also evidence that the regional climate anomalies associated with El Niño conditions increase the risk of certain vector-borne diseases, such as malaria, in places where they don’t occur every year and where disease control is limited.

El Niño sometimes brings drought to Africa’s Sahel.

However, while we may expect certain climate impacts in certain regions during an El Niño event, there is still a possibility that other aspects of the climate system in a particular year may work to offset the influence of El Niño. During either an El Niño or a La Niña, we also observe changes in atmospheric pressure, wind and rainfall patterns in different parts of the Pacific, and beyond. An El Niño is associated with high pressure in the western Pacific, whereas a La Niña is associated with high pressure in the eastern Pacific. The ‘see-sawing’ of high pressure that occurs as conditions move from El Niño to La Niña is known as the

Southern Oscillation. The oft-used term

El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, reminds us that El Niño and La Niña episodes reflect changes not just to the ocean, but to the atmosphere as well. For more details on ENSO, please visit the International Research Institute for Climate and Society’s

official ENSO page.

ENSO is one of the main sources of year-to-year variability in weather and climate on Earth and has significant socioeconomic implications for many regions around the world. The developing El Niño conditions in recent months offers an opportunity to clear up some common misconceptions about the climate phenomenon:

[h=3]1. Do El Niño periods cause more disasters than normal periods? On a worldwide basis, this isn’t necessarily the case. But ENSO conditions do allow climate scientists to produce more accurate seasonal forecasts and help them better predict extreme drought or rainfall in several regions around the globe. (Read a 2005 paper on the topic

here.) On a regional level, however, we’ve seen that El Niño and La Niña exert fairly consistent influences on the climate of some regions. For example, El Niño conditions typically cause more rain to fall in Peru, and less rain to fall in Indonesia and Southern Africa. These conditions, combined with socioeconomic factors, can make a country or region more vulnerable to impacts. On the other hand, because El Niño enhances our ability to predict the climate conditions expected in these same regions, one can take advantage of that improved predictability to help societies improve preparedness, issue early warnings and reduce possible negative impacts.

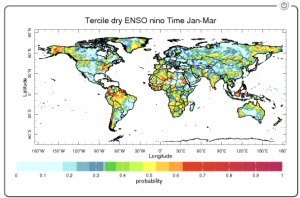

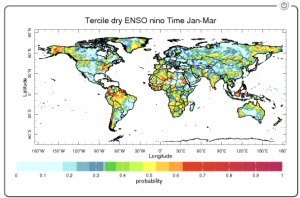

This set of interactive maps from IRI’s Data Library shows the historical tendency of El Niño and La Niña to affect seasonal precipitation around the world.

[h=3]2. Do El Niño and La Niña significantly affect climate in most regions of the globe? They significantly affect only about 25% of the world’s land surface during any particular season, and less than 50% of land surface during the entire time that ENSO conditions persist.

[h=3]3. Do regions affected by El Niño and La Niña see impacts for the entire 8-12 months that the climate conditions last? No. Most regions will only see impacts during one specific season, which may start months after the ENSO event first develops. For example, the current El Niño may cause the southern U.S. to get wetter-than-normal conditions in the December to March season, but Kenyans may see wetter-than-normal conditions between October and December.

Walter Baethgen discusses the ‘winners and losers’ in agriculture during El Niño

[h=3]4. Do El Niño episodes lead to adverse impacts only? Fires in southeast Asia, droughts in eastern Australia, flooding in Peru often accompany El Niño events. Much of the media coverage on El Niño has focused on the more extreme and negative consequences typically associated with the phenomenon. To be sure, the impacts can wreak havoc in some developing and developed countries alike, but El Niño events are also associated with reduced frequency of Atlantic hurricanes, warmer winter temperatures in northern half of U.S., which reduce heating costs, and plentiful spring/summer rainfall in southeastern Brazil, central Argentina and Uruguay, which leads to above-average summer crop yields.

[h=3]5. Should we worry more during El Niño episodes than La Niña episodes? Not necessarily. They each come with their own set of features and risks. In general, El Niño is associated with increased likelihood of drought throughout much of the tropical land areas, whereas La Niña is associated with increased risk of drought throughout much of the mid-latitudes (see maps

here and

here.) El Niño may have gained more attention in the scientific community, and thus the public, because it substantially alters the temperature and circulation patterns in the tropical Pacific. La Niña, on the other hand, tends to amplify normal conditions in that part of the world: the relatively cold temperatures in the eastern equatorial Pacific become colder, the relatively warm temperatures become even warmer, and the low-level winds blowing from east to west along the equatorial Pacific strengthen.

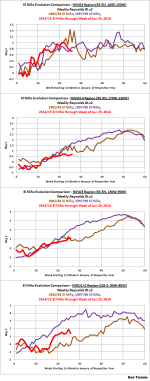

[h=3]6. The stronger the El Niño/La Niña, the stronger the impacts, and vice versa, right?

Current forecasts show that a weak-to-moderate El Niño is likely to develop by mid-autumn 2014. Does this mean we should expect weak-to-moderate impacts? Not necessarily. The important point to remember is that ENSO shifts the odds of some regions receiving less or more rainfall than they usually do, but it doesn’t guarantee this will happen. For example, scientists expected the very strong El Niño of 1997/98–which triggered wildfires in Indonesia and flooding and crop loss in Kenya – to also increase the chances of below-normal summer rainfall in India and South Africa, but this didn’t happen. On the other hand, India did experience strong rainfall deficiencies during a much weaker El Niño in 2002, and severe drought during the moderate El Niño of 2009-2010. So, while there is a slight tendency for stronger El Nino/La Niña events to have stronger impacts, many exceptions may be expected.

[h=3]7. Are El Niño and La Niña events directly responsible for specific storms or other weather events? We usually can’t pin a single event on an El Niño or La Niña, just like we can’t blame global climate changes for any single hurricane. ENSO events typically affect the frequency or strength of weather events–for example. when looked at over the course of a season, regions experience increased or decreased rainfall.

[h=3]8. Are El Niño and La Niña closely related to global warming? El Niño and La Niña are a normal part of the earth’s climate and have likely been occurring for millions of years. Global climate change may affect the characteristics of El Niño and La Niña events, but the research is still ongoing.

Thanks to Lisa Goddard and Anthony Barnston for lending their expertise and for reviewing this article.